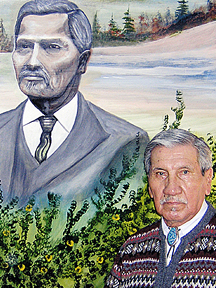

Joseph Nicolar and his Daughters

by Charles Norman Shay as presented at the University of Maine September 25th, 2006.

Pat and Charles Norman ShayWe are here to-day to discuss the life of Joseph Nicolar, author of “Life & Traditions of the Red Man”, but before we start I would like to bring your attention to a few facts that concern the Penobscot Indians who now reside on a small island in the Penobscot river at Old Town. When the first European settlers set foot on the shores of the so-called “New World” at the beginning of the 1600s, the Penobscot, it was estimated, numbered as many as 50,000 individuals. These numbers were drastically reduced over the years by hunger, a result of the disruption of life of the native people. Wars, between rival factions, which also involved the Native American. Alcoholism brought on as a result of the introduction of alcohol by the settlers. And lastly, diseases, which were prevalent in Europe but did not exist in the “new World”, decimated the region’s Native American population almost to a point of no recovery. As a child I can remember when the total population of our small reservation hovered around 500 individuals.

Pat and Charles Norman ShayWe are here to-day to discuss the life of Joseph Nicolar, author of “Life & Traditions of the Red Man”, but before we start I would like to bring your attention to a few facts that concern the Penobscot Indians who now reside on a small island in the Penobscot river at Old Town. When the first European settlers set foot on the shores of the so-called “New World” at the beginning of the 1600s, the Penobscot, it was estimated, numbered as many as 50,000 individuals. These numbers were drastically reduced over the years by hunger, a result of the disruption of life of the native people. Wars, between rival factions, which also involved the Native American. Alcoholism brought on as a result of the introduction of alcohol by the settlers. And lastly, diseases, which were prevalent in Europe but did not exist in the “new World”, decimated the region’s Native American population almost to a point of no recovery. As a child I can remember when the total population of our small reservation hovered around 500 individuals.

Although I never knew my grandfather personally (he died almost thirty years before I entered this world), I somehow feel a spiritual connection to him. I recall as a child, a large framed picture of him hanging above the piano in our living room. Trying to gather information I often questioned my mother as to who he was and what he was like as a person. I would now like to share with you a little of what I learned.

Joseph Nicolar was born on the 15th of February 1827, the son of Tomar Nicolar and Mary Malt Neptune and one of six siblings. His mother was the daughter of Lt. Gov. John Neptune, a hereditary chief.

Joseph Nicolar was born on the 15th of February 1827, the son of Tomar Nicolar and Mary Malt Neptune and one of six siblings. His mother was the daughter of Lt. Gov. John Neptune, a hereditary chief.

Little is known about Joseph's early childhood, but we do know that his father died when Joseph was only ten years old, making it necessary for him to assume the role of man of the house and to assist in providing for the family. In the year of 1840, twenty years after Maine became a state, his mother wrote a letter to His Excellency the Governor and the Honorable Council of the State of Maine seeking assistance for the education of her son Joseph. Joseph was mainly self-educated up to the age of thirteen, but still with no formal education he was able to read the bible, “pretty well” according to his mother. Research shows that Joseph by his own statements eventually, through the influence of a Mr. Packard, attended school in Rockland and then later in Warren, Brewer and Old Town. It has been said that he probably had the best education of all Penobscot Indians of his time.

With his gift for oration and his hard earned writing skills, he soon began contributing news items and brief articles, in the 1870s, to local newspapers using the initials YS (Young Sabattus) as a signature. Later he wrote articles on tribal arts, crafts and history for an Old Town newspaper.

It is not known when Joseph began his work on The Life & Traditions of the Red Man, but it is assumed to be quite late in his life. The book, of which I have an original first edition copy, was printed in 1893 by C.H. Glass & Company of Bangor, Maine and bound in hard cover, dark green in color. On the spine of the book in gold letters one reads “The Red Man” and just below that “Nicolar”. The frontispiece of the book features a photograph of a very dignified man in a suit with necktie, my grandfather, ‑ the very picture that once hung above the piano in our living room.

Joseph probably had to pay for the publication fees himself so therefore the print-run could not have been very large. Unfortunately, most of the copies of this book were destroyed in a warehouse fire and today very few copies of the original print run are still in existence.

Joseph married Elizabeth Joseph and together they had three daughters. Emma was born in 1868. Lucy was born in 1882 and Florence 1884. Emma, who was housewife and mother to nine children, was in some ways like my mother Florence, very reserved, never uttering a harsh word and a good mother to her children. She and her family were our next-door neighbors and I visited often as a child.

Florence Nicolar Shay at approx. 19yrsFlorence, my mother, was in contrast to her sister Lucy, who I will discuss later, very quiet and reserved. She was an avid piano player, a lover of classical music and a master in the art of basketry. In late 1929, following the stock market crash and the great depression that followed, my parents, who had been living and working in Bristol, Connecticut for the past eight years, were forced to move back to their home on the Indian Reservation at Old Town, Maine for lack of employment in Connecticut. In order to find a way to support their large family they returned to weaving and selling baskets made of brown ash and sweet grass, but the reservation was not the ideal place for such a business because too many of the residents were doing the same thing and as we had no connecting bridge to the main land, visitors and customers were very scarce. It was then that my parents drove up and down the coast looking for the ideal spot to set up a small shop and when they came to Lincolnville Beach on Penobscot Bay they knew immediately that they had found what they were looking for.

Florence Nicolar Shay at approx. 19yrsFlorence, my mother, was in contrast to her sister Lucy, who I will discuss later, very quiet and reserved. She was an avid piano player, a lover of classical music and a master in the art of basketry. In late 1929, following the stock market crash and the great depression that followed, my parents, who had been living and working in Bristol, Connecticut for the past eight years, were forced to move back to their home on the Indian Reservation at Old Town, Maine for lack of employment in Connecticut. In order to find a way to support their large family they returned to weaving and selling baskets made of brown ash and sweet grass, but the reservation was not the ideal place for such a business because too many of the residents were doing the same thing and as we had no connecting bridge to the main land, visitors and customers were very scarce. It was then that my parents drove up and down the coast looking for the ideal spot to set up a small shop and when they came to Lincolnville Beach on Penobscot Bay they knew immediately that they had found what they were looking for.

They were very fortunate in finding a very congenial property owner who had a vacant lot on the main road directly across from the beach and the lobster pound, a restaurant located in the beach area, and he agreed to rent this piece of property to my father at a very reasonable fee. The lobster pound from that era is still in existence today. However, because my parents did not have the finances to construct a wooden building to be used as a small shop, they bought and set up two canvas tents end to end. One was to be used as a sales room and one to be used as living quarters. These were very difficult times for our small family, mother and father with two young boys. At the beginning we had no electricity or water, but fortunately there was a public water pump nearby and we used kerosene for lighting and heat. As business began to pick up my parents were able to rent a small apartment from our landlord and we were able to live more comfortably. My mother died at Lincolnville Beach in May 1960 and my father continued to operate the business until 1966 when he sold out to one of his grandsons who continued to operate the business until the end of the season in 1999. This small business had been in operation for almost seventy years.

During her life, my mother was a strong and active advocate of various legal rights for her people. One of them was the right for parents to send their children to any elementary school in the area of the reservation. A bridge connecting the reservation to the main land and the right to vote in state and federal elections were two other items that were on the agenda of my mother. I do not want to leave you with the impression that my mother was the only advocate of these rights for our native people. This was a joint effort of many of the elders of her time. Although we had our own grade school on the reservation, my mother was of the opinion that too much emphasis was being place on religion and not on an education the would prepare the children for high school and possibly the opportunity to continue on to college or university. Not one to wait to be told what she should do with her own children when it came to their education my mother insisted that I was to attend the public school in Old Town from the first grade on. Being the only Indian boy in a class of over forty children was a difficult time for me, but I soon managed to overcome my shyness and became an accepted classmate and eventually had many friends.

The first bridge, a one-way bridge, was built in November of 1950 and in 1986 was replaced by a spacious two lane bridge, The Penobscot was finally able to travel at will by automobile directly from his front door and we were no longer confined to our little reservation. It was celebrated as a great achievement.

Bruce Poolaw and Lucy Nicolar PoolawIn 1954, we were finally granted the right to vote in federal elections and not until 1967 did the way become clear for the Penobscot to vote in state and local elections.

Bruce Poolaw and Lucy Nicolar PoolawIn 1954, we were finally granted the right to vote in federal elections and not until 1967 did the way become clear for the Penobscot to vote in state and local elections.

Lucy was the typical extrovert who enjoyed being in the limelight. This aspect of her character played an important part in her future life. At an early age she took on the stage name of “Princess Watahwaso” and during the 1920s toured the country with Bruce Poolaw, a Kiowa Indian from Oklahoma performing dances and songs of Indian origin and introducing the culture and history of her people to her audience. Lucy and Bruce became man and wife later on in life. Promotional materials for her performances described her as “supreme in the portrayal of Indian Lore and in the interpretation of Indian music”.

However, Lucy and Bruce also became victims of the stock market crash of 1929 and were forced to return to the Indian Reservation. They bought a choice piece of land and built their home, followed a few years later by a wooden structure that was constructed in the form of a “Teepee”. During the 1930s they continued to be active in show business in the Sate of Maine by visiting tourist resorts and summer camps, putting on exhibitions of Indian songs and dances during the evenings for the entertainment of the guests. In addition, at each of these engagements, they were permitted to erect a small stand where Indian baskets, moccasins and novelties were displayed and sold. As a child I was part of the entertainment team doing my bit as a young Indian dancer – known as “Little Muskrat” thanks to my Aunt Lu. The “Teepee, as mentioned, above was constructed beside their home in 1947 and was used as an Indian novelty shop.

Lucy died in 1969 and her husband Bruce remained on Indian Island for approximately 2 years before returning to his native Oklahoma where he eventually passed on.

In 1988 I came into possession of the property and, after making many necessary repairs, converted the “Teepee” into a small family museum dedicated to my ancestors. The walls and ceiling are covered with murals painted by Calvin Francis, a young and very talented Penobscot artist. The murals depict family members and also various animals that are common to the State of Maine.

Through my research, I now know that my grandfather was a gifted orator, reporter and an elected official of the Penobscots. He held the position of tribal representative to the State Legislature a total of eight times. According to my mother the expertise of both grandparents was often sought to settle disputes and/or to seek advice and assistance with personal problems that sometimes arose involving members of our small community.

A picture, taken of my grandfather shortly before his death, shows him as having aged very rapidly and gives the impression that he was a very sick man. My grandfather died on the 14th of February 1894 at the age of 67 years.

In conclusion, I would like to say that Joseph Nicolar became a legend in his own right and that the Penobscots should be very proud of one of their own who persevered at a time when the Native Americans were regarded as unworthy of recognition, regardless of what they had accomplished in life. He was a true inspiration to his people having proved that an education, regardless of how little, was the key to rise above the oppression that was being experienced by Native Americans at the time. Otherwise we were destined to remain second class citizens in our own country the rest of our lives.

Little has been said about Elizabeth Joseph Nicolar, wife to Joseph and the mother to their three daughters. Elizabeth had a very strong influence in the family, especially on her daughters. From their mother they learned the art of basket weaving, the importance of a proper education and that the Native American was entitled to all of the rights that were bestowed to the rest of the citizens of the country. Lizzie, as she was called, was twenty years younger than Joseph. She was described by a local newspaper as being an individual “respected,” intelligent”, and “superior in many ways”. Lizzie traveled throughout New England marketing the baskets produced by herself and her two daughters (Lucy and Florence) and eventually these travels involved sportsman shows that were held in Boston, Chicago and Baltimore. Lizzie was a born leader. She helped found the Wabanaki Club of Indian Island in 1895, which gained membership in the State Federation of Women’s Clubs in 1847 and she was elected its first vice president. Florence, with her sisters Lucy and Emma and sister-in-law Pauline Shay, activated the Women’s Club again in the early 1930s to promote “welfare, education and social progress” for their people and they were once again affiliated with the Maine Federation of Women’s Clubs, as well as with the National Federation. It is very apparent that Joseph and Elizabeth willingly took on the responsibility for the welfare of their people and were able to accomplish very much during their lives, all to the benefit of their family and their people.

Coming to a close, I would like to dedicate these words, this short family history that I have just conveyed to you, to my forefathers and, not to forget, my foremothers. I did not find this word in the dictionary but I use it anyway because of the very important role these women played in the lives of their children. They were very active and determined individuals when anything pertaining to the welfare and civil rights of their families was at stake.

I would now like to send a message to them. I will call it “A Spiritual Message of Admiration and Respect for my Ancestors”. I bow my head in a moment of respect to our ancestors, both yours and mine.

Charles Norman Shay (Penobscot)

Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur