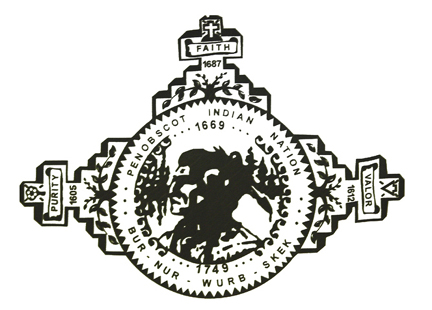

The seal which appears on the Penobscot Nation flag was designed by Senabeh Francis in the mid 1970's. The center of the seal is an un-named Penobscot warrior. Surrounding the warrior is an ornate border which contains three 'tombstones' adorned with crosses.

The top tombstone has "FAITH" written on the cross, and above is a smaller cross. These elements along with the date 1687, the date of the first Catholic mission on IndianIsland, honor our history with the French Jesuits and other clergy of the Catholic Church as well as other denominations. Faith is synonymous with trust and belief.

The left tombstone has “PURITY” written on the cross of the tombstone. Above that is a flower, a daisy which is a symbol for purity. Below is the date 1605. This marks the year when Captain George Weymouth, an explorer for England, kidnapped five Penobscot warriors so he could teach them to speak English, to communicate with them better. Purity signifies our dedication to remain a distinct culture, even in the face of acts like these.

The right tombstone has “VALOR” written on the cross. Above that is an arrowhead. This tool was an important tool in the defense of our culture and people.The date 1612 marks a year during wartime. The valor, meaning bravery in the face of danger, shows how Penobscots have fought bravely for their people.

These three virtues comprise what has been called the ‘tribal motto.’

At the base of each of these tombstones, outside the circle, are three branches representing tribal growth.

Two dates appear above and below the image of the warrior. The top date, 1669, commemorates the war with the Iroquois. The lower date, 1749, denotes the date of a treaty of peace with Massachusetts Bay Colony, ending King George’s War. Together along with twelve double-curves, (representing fire-starters/flint) represents the balance between war and peace and the wisdom of our twelve elected council members.

The serrated edge denotes the sun. We are Wabanaki, a people of the dawn.

The Penobscot Nation and Passamaquoddy Tribe of Indians have representatives in the Maine State Legislature. Below is a brief history written by S. Glenn Starbird, Jr. and updated by Passamaquoddy Representative Donald Soctomah and former Penobscot Representative Donna M. Loring. Along with this narrative is an extended list of Penobscot Representatives who served in the past. The current Penobscot Representative is Wayne T. Mitchell.

The Penobscot Nation and Passamaquoddy Tribe of Indians have representatives in the Maine State Legislature. Below is a brief history written by S. Glenn Starbird, Jr. and updated by Passamaquoddy Representative Donald Soctomah and former Penobscot Representative Donna M. Loring. Along with this narrative is an extended list of Penobscot Representatives who served in the past. The current Penobscot Representative is Wayne T. Mitchell.

Pictured: Joseph Nicolar, Penobscot Representative: 1859, 1860, 1865, 1873, 1881, 1885-86, 1889-90, and 1893-94.

Joseph Nicolar died February 15, 1894 while serving as Penobscot Representative.

A Brief History of Indian Legislative Representatives in the Maine Legislature by S. Glenn Starbird, Jr., 1983.

Updated by Donald Soctomah, 1999, and by Donna M. Loring, 2001

The earliest State of Maine record that representatives were sent from the Penobscot Nation is in 1823, and from the Passamaquoddy Tribe, 1842. At that time, there was no state law regarding election of Indian delegates or representatives to the legislature and the choice of this person or persons was determined by tribal law or custom only. Massachusetts records show that the practice of the two tribes sending representatives to the legislature was not new with the formation of the State of Maine in 1820, but probably had been going on since before the Revolutionary War.

The differences between the Old and New parties in the Penobscot Nation caused such confusion that the two parties signed an agreement in 1850 which provided, among other things, that "an election should be held every year to choose one tribal member to represent the tribe before the legislature and the governor and council." This agreement governed the choice of representative until the legislature passed the so-called "Special Law" of 1866, which, with the tribe’s agreement, finally settled the procedures for election for not only its representative but for governor and lieutenant governor (now known as chief and sub-chief) as well.

A similar agreement setting forth the form of their tribal government was made between the two Passamaquoddy reservations in what is known as the "Treaty of Peace of 1852." The system of government established by this document has remained unchanged in its essential provisions ever since, although it was not enacted into state law until the Passamaquoddy Tribe petitioned the legislature to do so in 1927. Among the Passamaquoddy, the representative was to be elected alternately from each of the reservations. The Passamaquoddy have two reservations, Sipayak (Pleasant Point) is located near Perry, Maine, and Indian Township near Princeton, Maine.

Over the last half of the nineteenth century there was a gradual growth and development of the Indian representatives’ status in the legislative halls. Only from the middle 1890s was there verbatim legislative record made, and not until 1907 was it provided with an index, but from that year on we can read clearly the record in session after session where the Indian representatives were seated, sometimes spoke, and were accorded other privileges.

This gradual improvement in their status resulted in an effort during the 1939 legislature to place Indian representatives on a nearly equal footing with the others. This effort failed, however, and the 1941 session passed legislation that ousted the Indians entirely from the hall of the house, reducing their status to little better than state-paid lobbyists. Since 1965, however, a gradual change for the better has occurred. Salaries and allowances have increased, and seating and speaking privileges were restored in 1975, after a lapse of thirty-four years.

The closest analogy to Indian representation in the Maine State Legislature now existing is probably the federal laws that allow the territories and the District of Columbia to seat delegates in the federal House of Representatives. Under federal law and House rule, a delegate can do anything a regular House member can do except vote on pending legislation. He/she can sit on a committee and vote in committee; he/she receives the same salary and allowances; and for all practical purposes, except the House vote, does what any member of Congress can do.

Opinions by the Office of the Maine Attorney General over the years seem to support the position of Indian representatives in the Maine legislature as very similar to delegates of the territories in Congress under the law and house rules as they now stand. At any rate, it is to be hoped that improvements in status will continue, for with the settlement of the Maine Indian land claims in 1980 establishing an entirely new relationship with the state, the need for competent representation of the Indian tribes in the legislature is more vital than ever.

In 1996 the tribal representatives sponsored a Native bill for the first time ever, and in 1999 a rule change allowed the Passamaquoddy and Penobscot representatives to cosponsor any bill, statewide.

As of 2001 there were several provisions in statute and in the House Rules and Joint Rules related to the rights, privileges, and duties of the tribal representatives1.

The provisions are these:

3 MRSA subsection 1

3 MRSA subsection 2

Rules of the House, Rule 5252

Joint Rules, Rule 206 (3)

Under these provisions tribal representatives:

- Must be granted seats in the house;

- Must be granted the privilege, by consent of the speaker, of speaking on pending legislation;

- Must be appointed to sit as nonvoting members of joint standing committees;

- May sponsor legislation specifically relating to Indians and Indian land claims, cosponsor any other legislation, and either sponsor or cosponsor expressions of legislative sentiment;

- May be granted any other rights and privileges as voted by the house;

- May amend their own legislation from the floor of the house;3 Are entitled to per diem and expenses for each day’s attendance during regular sessions and to the same allowances as other members during special sessions.

The Wisconsin, New Brunswick, and New Zealand legislatures are reviewing Passamaquoddy and Penobscot representative status to use as a possible model. The results of those studies are unknown at this time.

Note: The above narrative concerning Indian representation in the legislature is based on information derived from the legislative record, federal and state rules, State Department reports, Maine public laws, resolves, private and special laws, federal laws, newspaper articles, and other published accounts.

1 Final Report of the Committee to Address the Recognition of the Tribal Government Representatives of Maine’s Sovereign Nations in the Legislature

2 The Joint Standing Committee on Maine’s Sovereign Nations Native Representation is the most recent in-depth study of the duties and history of the tribal representatives. It sets forth recommendations to both houses of the legislature, which to date have been ignored.

3 This was the latest joint rule to be past during the 120th legislative session.

Penobscot Representatives

Names are spelled as they appeared in the legislative record, where they were often misspelled. Assistance correcting these errors was provided by Carol Binette, Penobscot Nation. 1823 Francis Loran [Lolar] and John Neptune

1824 John Attean, John Neptune, and Francis Loran [Lolar]

1831 John Neptune and Joseph Soc Basin [Sockbasin]

1835 John Neptene [Neptune], Jo [Joseph] Sockbasin, Peol Malley [Molly]

1836 Joe [Joseph] Sockbasin, Joe [Joseph] Porus [aka Polis], John Peol Susop [Susep], Peol Tomer

1837 John Neptune, Peol Tomer, Nuil Luey [Newell Lewey]

1842 Joe [Joseph] Porus [aka Polis], Joe Socabeson [Joseph Sockbasin], Peol Newell

1844 Peol Porus [aka Polis], Joseph Socabasin [Sockbasin], John Neptune

1850 Attean Lola [Lolar], Joe [Joseph] Sockbasin, Joseph Porus [aka Polis]

1851 Attean Lolah [Lolar], Representative

1853 Peol [Peal] Sockis

1854 Peol [Peol] Sockis, Representative, Attean Orson, Special Agent of Tribe

1855 Peol [Peal] Sockis, Delegate

1856 Joseph Socabasin, Delegate

1857 Socabeson Swasson [Sockabesin Swassian] attending legislature; Peol [Peal] Sockis, Delegate

1858 Peol [Peal] Sockis, Representative

1859 Joseph Nicolar, Representative

1860 Joseph Nicolar, Representative

1861 Peol [Peal] Sockis, Representative

1862 Joseph Nichola [Nicolar], Representative

1863 Peol [Peal] Sockis, Representative, Joseph Sockbasin serves Commissioner of Indian Affairs

1864 Peol [Peal] Sockis, Representative

1865 Joseph Nicolar, Representative

1866 Joseph Lewis Orono, Representative; Peol [Peal] Sockis, before legislature for tribe

1867 Peol Mitchell Francis

1868 Sockabasin [Sockabesin] Swassian, Delegate

1869 Saul Neptune , before legislature

1870 Joseph N. Soccalexis [Joseph Mary Sockalexis], before the legislature

1871 Newel [Newell] Neptune, Representative

1872 Sockbesin Swassin [Sockabesin Swassian], Representative

1873 Joseph Necolar [Nicolar], Representative

1874 Joesph N. Socklexis [Joseph Mary Sockalexis], Delegate

1875 Mitchell Paul Susus [Peal Mitchell Susep], Delegate

1876 Joseph Francis, Representative

1877 Sebbatis [Sabattis] Dana, Representative

1878 Joseph N. Soccalexis [Joseph Mary Sockalexis], Representative

1879 Sabbatus [Sabbatis] Dana, Representative

1880 Lola Cola [Coley; actual surname is Nicola], Representative

1881 Joseph Nicolar, Representative

Two-year terms begin

1882 Lola Cola [Coley; actual surname is Nicola], Representative

1885 Joseph Nicolar, Representative

1887 Lola Cola [Coley; actual surname is Nicola], Representative

1889 Joseph Nicolar, Representative

1891 Lola Cola [Coley; actual surname is Nicola], Representative

1893 Joseph Nicolar, Representative

1895 Lola Cola [Coley; actual surname is Nicola], Representative

1897 Horace Nicola, Representative

1899 Sabatis Shay, Representative

1901 Thomas Dana, Representative

1903 Joseph Mitchell, Jr.

1905 Peter N. Nelson [Peter Mitchell Nelson]

1907 Nicholas Sockabasin [Nicola Sockbeson]

1909 Charles Daylight Mitchell

1911 Lola Cola [Coley; actual surname is Nicola]

1913 Peter Ranco

1915 Leo Shay (first time election)

1917 Peter W. Ranco (Old Party)

1919 Mitchell M. Nicolar

1921 Horace Nelson. First mention by speaker, who said, “The chair extends the welcome of the house of representatives to the representative of the Penobscot Tribe of Indians who is now seated in your body.”

1923 Joseph P. Lewis (“Mr. Lewis is now in his seat with us in the rear of the hall.” Applause.)

1925 Newall Gabriel, escorted to chair amid applause. Members rising.

1927 Lawrence Mitchell

1929 John Nelson, house messenger escorted him to his seat amid applause.

1931 James Patrick Lewis, assigned seat 150 by speaker.

1933 Elmer Attean, was seated. House order gave both Indian representative stamps and telephone cal credit cards

1935 John Sebastian Nelson, seated Number 151 and conducted there by the sergeant-at-arms amid applause of the house.

1937 John Sebastian Nelson

1939 Leo Shay

1941 Harold Polchies. A Bill was introduced to change the words “Representative to the Legislature” to “Representative at the Legislature.” Indian Representatives were, prior to this date, allowed to sit in the house hall and speak.

1943 James Lewis. He was conducted to the center aisle and greeted by the speaker, at which time he thanked the speaker for acknowledgment.

1945 Harold Polchies

1947 Harold Polchies

1949 Ernest Goslin

1951 John Sebastian Nelson

1953 John Mitchell

1955 Francis Ranco

1957 John Nelson was tribal representative serving through 1957, 1959, 1961, 1965, and 1969 sessions.

1971 John Murray Mitchell, Sr., elected in December 1970 in a special election to succeed John S. Nelson

1973 Vivian F. Massey, ran on a write-in ticket in September 1972 and won by four votes after a recount. She was the first women to ever be elected Indian Representative.

1975 Ernest Goslin. On January 22, 1975, the Maine House of Representatives voted to seat the Indian Representatives and give them speaking privileges by a vote of 107 to 40, thus ending a ten-year effort to restore the rights taken from Indian Representatives by the 1941 legislature. Ernest was reelected in 1976 for the term 1977-78.

1979 Timothy Ray Love

1980 Reuben Elliot Phillips

1983 James Gabriel Sappier

1984 Priscilla Ann Attean, serving through the 1987, 1989, 1991, and 1993 sessions.

1995 Paul Joseph Biscula

1997 Paul Joseph Biscula, served the first session and the resigned.

1997 Donna Marie Loring, elected in a special election.

1999 Donna Marie Loring, reelected and served in 2001, 2002, and 2004.

2005 Michael Joseph Sockalexis, elected but ill for first three months of the session. Donna Marie Loring took over as alternate representative.

2007 Donna Marie Loring, reelected.

2009 Wayne T. Mitchell

It is said that when Gluscap first came into this land of the Wabanaki, next to sunrise, he "came from nothing." According to Penobscot author Joseph Nicolar, “Klose-kur-beh, ‘The Man from Nothing,’ first called the minds of the ‘Red Children’ to his coming into the world when the world contained not other man, in flesh, but himself. When he opened his eyes lying on his back in the dust, his head was toward the rising of the sun...”

It is said that when Gluscap first came into this land of the Wabanaki, next to sunrise, he "came from nothing." According to Penobscot author Joseph Nicolar, “Klose-kur-beh, ‘The Man from Nothing,’ first called the minds of the ‘Red Children’ to his coming into the world when the world contained not other man, in flesh, but himself. When he opened his eyes lying on his back in the dust, his head was toward the rising of the sun...”

Upon his arrival, Gluscap was greeted by Nokomis, his Grandmother and she took him in. Nokomis raised Gluscap and he afforded her the utmost respect. Through Grandmother’s guidance and teachings Gluscap learned to live in balance. Her teachings contained cultural values that were woven throughout Wabanaki oral history and are witnessed in the upbringing of Gluscap.

At that point there were no other Wabanaki here in the land of the dawn. Before people, Gluscap created the little people, dwellers in rocks. It was to these creatures that Gluscap first conveyed the values he learned from Nokomis. The little people later shared this knowledge.

Next, Gluscap took his bow and arrows and shot at trees, particularly the basket trees (the ash). This tree has been woven, interlocking our past with our future and providing sustenance to our present. The arrow struck the ash tree and split it. From this split came the first man and the first woman and all the animals of the land.

The animals that Gluscap created were created too large or fierce. Many subsequent legends feature Gluscap transforming the animals and teaching Wabanaki people how to live in balance and harmony with these creatures. Also many legends feature little people, sharing the knowledge they learned.

The role of women is very important, central, and integral to Penobscot society, both in the past and in the present. From the beginning of our creation the role of the women has been central to health and balance of Penobscot people. Her role was prominent throughout our history. It was the women who raised chiefs and was the child’s first teacher. The women raised the children and watched them grow up, and so were in a good position to watch for upcoming leaders. The eldest female oversaw all domestic affairs of the family, and the Chiefs were wise to listen to the grandmothers. Grandmother’s powers were highly regarded and respected.